White-nose syndrome (WNS), a fungal pathogen caused by Pseudogymnoascus (formerly Geomyces) destructans, was first identified in 2006, and has since been associated with the deaths of over 6 million bats here in North America. This devastating fungal infection may be present even when no obvious signs are seen. Therefore, we as rehabbers must be aware of any potential infection and act accordingly with isolation and care to prevent the build up or spreading of the fungal spores within our facilities. The U.S. Geological Survey’s National Wildlife Health Center has tested the use of UV light to detect WNS in bats. The good news is that by simply evaluating the bat using a UV light, nearly 99% of WNS cases were detected, and 100% of bats that tested negative, were indeed, negative for the disease. 1 That means that we can use this tool with confidence as we admit bats to our care.

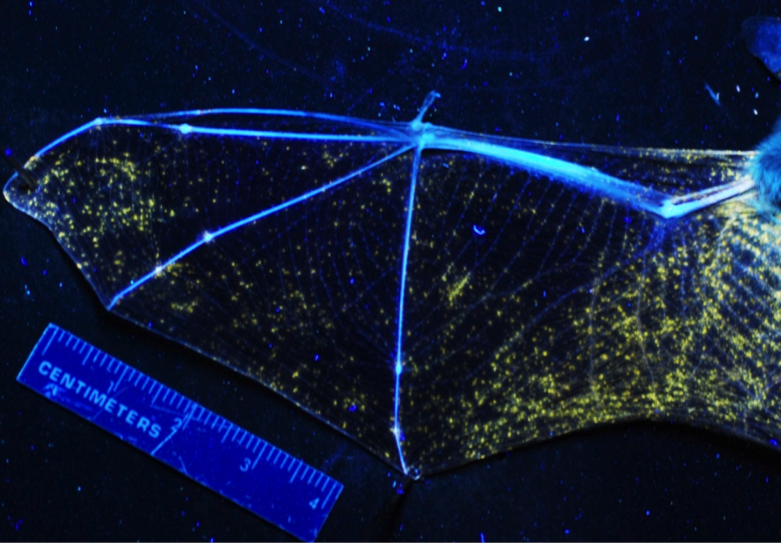

Buy an appropriate UV light. I checked and there are suitable models ranging from about $20 to several hundred dollars on Amazon. Be sure that the unit you buy works at the required light range of 385nm. Use this in a darkened area and explore all surfaces of the bat for signs of orange-yellow fluorescence indicating microscopic lesions associate with WNS as seen in the following photo.

If you have a positive result, your bat care should include isolation and appropriate cleaning to ensure you do not have a build up of these spores. The https://www.whitenosesyndrome.org/ website has a decontamination section which offers some great information, however, your standard cleaning agents may also be effective against fungal spores. So simply check the Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS) for your cleaning agent’s range of action.

The care and rehabilitation of animals infected with WNS are well covered in the following two documents; Rehabilitating Bats with White Nose Syndrome, and Protocol for Wildlife Rehabilitator Response to Hibernating Bats Affected with White-Nose Syndrome.

So in summary, this fungus is extremely widespread and any bat admitted, especially during the winter months, may be contaminated with microscopic lesions, which means every bat should be screened for WNS. Many of these bats are now members of shrinking populations and each animal represents an increasing percentage of the gene pool of that species, so we as rehabbers must do the very best for these animals as individuals. Also get to know your local researchers and become involved in the monitoring of the local bats. You will be able to bring your skills to the team and help when impacted animals require professional care. Finally, buy a UV light so you can simply screen your patients, not just on intake, but during the period of their care to ensure that if there are indeed developing lesions, you can act promptly, reducing any build-up of spores, and preventing it’s spread to others in your care. This is a great new tool for the rehabbers kit.

Reference:

1Gregory G. Turner, Carol Uphoff Meteyer, Hazel Barton, John F. Gumbs, DeeAnn M. Reeder, Barrie Overton, Hana Bandouchova, Tomáš Bartonička, Natália Martínková, Jiri Pikula, Jan Zukal, David S. Blehert. Nonlethal Screening of Bat-Wing Skin With the Use of Ultraviolet Fluorescence to Detect Lesions Indicative of White-Nose Syndrome. Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 2014; 140522114529005 DOI: 10.7589/2014-03-058

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.