The following is the third in a short series of posts from IWRC staff and board members who attended the WDA Conference at Granlibakken Resort in Tahoe City, California USA in August 2019

Multiple-drug resistance in wildlife

From the 2019 Wildlife Disease Association Conference, several presentations gave great cause for worry. The number of documented multi-antibiotic resistant infections in wildlife is increasingly more serious. Anthropogenic exposure is causing never-treated wildlife to host serious pathogens that will require specialized and aggressive antibiotic therapy; these organisms also could endanger rehabilitators and staff.

Wildlife as diverse as the kodkod, also called güiña (Leopardus guingna) in Chile and the California condors (Gymnogyps californianus) in California have microbial flora with multiple antibiotic resistance, reflecting the urban and agricultural environments in which they live.

Irene Sacristan and her team investigated antibiotic resistance genes in the güiña in Chile. PCR testing was used to identify genes associated with antimicrobial resistance; and since these genes are considered to be environmental contaminants, the results could be used to compare anthropogenic impact. The felines most exposed to human disturbance had the highest drug-resistant genes (including MRSA), but even pristine environments showed influence. The use of affordable PCR testing will become more and more important to diagnosis and characterization of diseases in our wildlife, and rehabilitators should be ready and educated for the time it actually happens.

Peter Sebastian and his team at UC Davis working with California condors examined cloacal E. coli (Escherichia coli) patterns of multiple-drug microbial resistance. The variation in the E. coli resistance depended upon the food source, and it is possible that those birds feeding on livestock carcasses may reflect antimicrobial resistance in livestock; and thereby environmental contamination.

Gulls in Alaska were shown to have multiple-drug antimicrobial resistance when their E. coli genome was sequenced. Christina Ahlstrom and collaborators found that trash-dump birds traveled locally and, by satellite tracking, were shown to travel as far south as southern California and East Asia. The potential of acquisition and dispersal of multi-drug resistant E. coli has many ramifications for human, environmental and animal health.

Marine mammals of the Salish Sea are being evaluated for multiple-drug resistant E. coli by Stephanie Norman and her collaborators. Seals and porpoises are showing evidence of such, and studies are on-going.

It is a lesson to all of us in wildlife rehabilitation to base antibiotic use on evidence: bacterial culture and antibiotic sensitivity should direct treatment, rather than just reaching for that vial of “xyz” for every animal. And a reminder that wildlife from urban and agricultural areas are highly likely to have resistant infections even if they never had antibiotics ever in their life! It is also a lesson for wildlife rehabilitators to collect good data and so contribute to research, disease survey and surveillance. And speaking of good data: every wildlife rehabber is important and can contribute significantly to both specific and overall knowledge bases. Early detection of disease or issues is at the doorstep of first-responder wildlife careers. Who are the boots-on-the-ground in the beginning of an outbreak, mortality, stranding, poisoning or other event? Several speakers mentioned the value of biologist/One-Health/disease surveillance collaborations with wildlife rehabilitation centers. It was gratifying to hear that the disease professionals value contributions from our community.

Pox viruses (Poxviridae) are an important disease for rehabilitators to understand. Amanda MacDonald and her team investigated pox viruses and found that different pox isolates are restricted to different taxa, but sporadic and evolving strains have the potential to infect more than one species. This information of extreme importance to managing outbreaks. For the rehabilitators, knowing these facts will help with bio-security and isolation policies.

Vaccine news

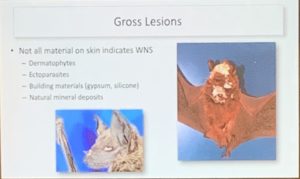

A lot is happening on the wildlife vaccine front. Real progress has been made on a White-nose syndrome with an oral, mass application carrier-virus vaccine for bats, and gives hope to the eventual protection of threatened populations and hibernacula.

Investigation into an effective oral formulation of anthrax (Bacillus anthracis) vaccine may be a good approach to protect wildlife in anthrax-endemic areas. Allison Fricht from Texas A&M University discussed the development of an oral anthrax vaccine for ruminants, wildlife and livestock. This is an important development to protect animals in regions where anthrax is endemic. The problem with ruminants is their many stomachs will denature oral vaccines and render them inactive or digested. Having a formulation that can be incorporated into feed or forage is a great advancement.

Vaccine trials in roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) with a tick vaccine show promise in controlling tick infestations in Spain, as described by presenter Isabel García Fernández de Mera.

Herps

Reptiles and amphibians were well-represented, with some great presentations on very frightening emerging and new diseases. Rehabbers especially in the southeast USA, but in reality, all across the globe, should be on the look-out for unusual oral and skin lesions in their herps. The diagnostic trail can usually start with a simple swab and finding the right lab. Fungal lesions are increasingly common, and some of the amphibian diseases thought to be ONLY in salamanders are now known to have the potential to infect anurans (frogs and toads). And sadly many of the novel diseases are likely related to the pet trade and trafficking, and “exotic” disease can appear anywhere and cause epidemics in local fauna.

Bunyavirus in turtles (softshells and cooters) – oral lesions and ulcers and plaques on other soft tissues along with severe internal organ lesions were examined by Lisa Shender and her team along the St. Johns River in Florida, USA. They discovered an underlying, new virus affecting all of them. The infection is similar and the virus is identical to one found in farmed turtles a number of years ago. Lethal new and emerging diseases are a serious threat to any vulnerable species and chelonians in general are under great threat and pressure.

It may seem esoteric, but having tissue culture cell lines from amphibians and reptiles is absolutely essential for detecting and diagnosis of diseases. Cell lines are very difficult from herps, and for many years there were only a handful of them in existence. Cell cultures are used especially in viral diseases and difficult parasites and demanding bacteria. Tracy Logan and her research team at the University of Florida were able to develop a number of lines that will be integral to diagnosis in herp diseases.

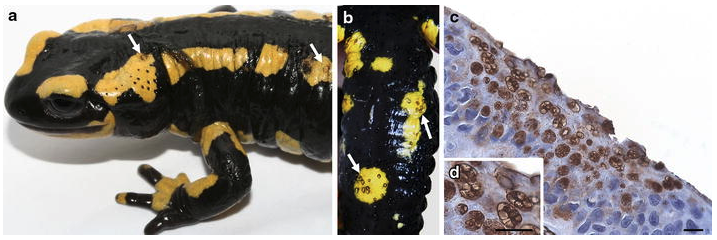

Truly horrifying and associated with climate change and animal trafficking and the exotic pet trade: serious, fatal fungal diseases. The chytrid fungus is well-known for debilitating disease in frogs and toads, but the Bsal (Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans) chytrid, infecting salamanders in Europe, may appear in the New World at any time. A team from the University of Tennessee looked into the possibility that Bsal not only could infect salamanders but potentially could spill over into frogs and toads. The animals developed typical lesions. This fungus could represent a serious threat to non-salamanders. Both this fungus and the other chytrid mycotic diseases in amphibians have been associated with legal and illegal trafficking of amphibians for the pet trade. Rehabbers should be alert to amphibian diseases, take appropriate samples, submit for testing, and be prepared for and assume all are highly contagious until proven otherwise.

Nicola Peterson and team from Australia were involved in a real-life detective story, tracing severe fungal disease in water dragons (Physignathus). Until very recently, mixed fungal diseases were described only from captive/pet animals. A recent outbreak in a city park is now confirmed from multiple locations. There is evidence that the original “patient zero” was a sick pet that was witnessed being released into the park. More reason than ever for rehabilitators to be vigilant, be aware that the pet trade adversely impacts wild populations, and to be prepared for multiple layers of diagnosis.

Hair!

Hair samples can be analyzed via spectrometry to reveal health status of populations. Hair is easy to collect, store, archive and identify. Jesper Moshbacher and many international collaborators analyzed trace elements from muskoxen (Ovibos moschatus) and showed that hair analysis was practical and useful tool, especially in remote and infrequently sampled regions.

Several talks concerned sarcoptic mange (Sarcoptes scabiei) outbreaks, which may have become a global crisis. From South America to California.

A team from the University of California Davis monitored a small population of endangered San Joaquin kit foxes (Vulpes macrotis mutica) and described potential routes of infection, den climate favorable to the mites, and proposed possible control measures. Another team from California Department of Fish & Wildlife compared various canid hosts and the genetic make-up of their mites, to determine if coyotes, foxes and dogs could be involved. They found the mites to be host specific and recommended treatment focusing on the kit foxes.

Chlamydia

Some frightening news has come out of California and Australia. Chlamydia infections are quite complicated and more sophisticated testing may be required. Not all Chlamydia are the same and novel species have been found in in native pigeon species and in raptors.

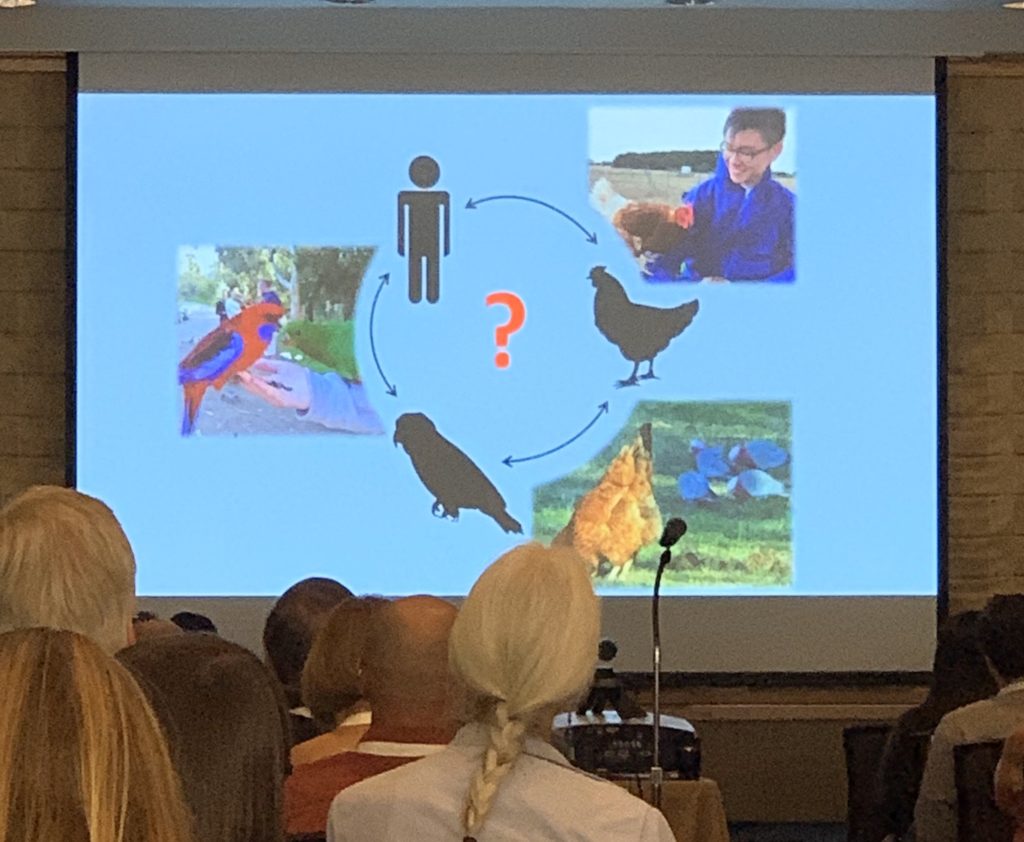

Helena Stokes and her team from Deakin University in Australia have found that infection by “regular” Chlamydia species in native parrots, people, and chickens can flow in all directions, with all pathogens and affect the host species in different ways. A lot more work needs to be done, including testing for novel species of Chlamydia.

Michelle Hawkins lead an investigation into characterizing and describing a new species of Chlamydia associated with severe disease in raptor species in California. It may be important to test sick birds for chlamydia by PCR and in addition request genome sequencing. Collaboration with investigators could be valuable.

Climate change

It was nice to hear from the world of invertebrates. We rehabbers may be asked to gain skills with invertebrate care and release in the near future, as climate crisis impacts more biodiversity. Ania Majewska from the University of Georgia investigated the protozoan parasites in Monarch butterflies in relation to urbanization.

Having been a fan of @WhiteAbalone since they started their Twitter account, I was thrilled to attend Blythe Marshman’s talk on white abalone (Haliotis sorenseni), an endangered species, and the rickettsial withering Syndrome. The presentation tied together the impact of overfishing, stress, changing water temperatures, and pathogen interactions. The care and compassion shown for the animals in their care was very inspiring.

Environmental conditions that favor algal overgrowth can be related to mass casualties in waterbirds. Corinne Gibble and her co-authors showed the brain pathology associated with both acute and sub-lethal toxin exposure.

Winner of the most uncomfortable award:

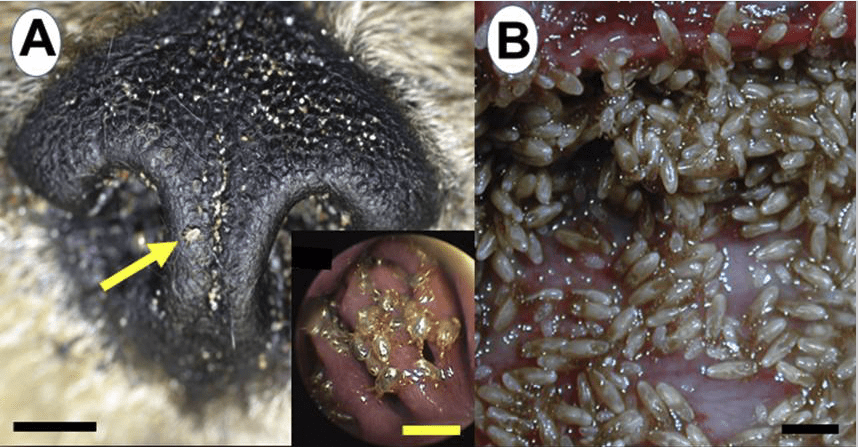

Colleen Shockling from Columbus Humane made a lot of the attendees squirm in their seats with descriptions and photos of nasal mites in southern sea otters. (NCBI link here) © 2019 The Authors – This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)

Tick world

Vectors and vectors-borne infections were the subject of a number of the talks. Francisco Ruiz-Fons and his team investigated Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) associated with ticks of the genus Hyalomma and red deer (Cervus elaphus) in southern Europe. This virus represents a possible threat to hunters and other humans who handle the animals (rehabilitators, veterinarians, etc). The disease may be widespread and rehabilitators should be aware of ticks, tick bites, and animals suffering from vector-borne disease.

Climate change and human activities may be influencing the distribution of ticks and their pathogens. In Norway, Carlos das Neves sampled many species of ungulates for hepatitis E and tick-borne encephalitis virus, both of which can infect humans and livestock, and demonstrated ungulates as valuable sentinels for early detection of emerging disease.

Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi) in upland game birds was detected in wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo), ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus), ring-necked pheasants (Phasianus colchicus), and American woodcock (Scolopax minor) from Pennsylvania, USA, and Christopher Cleveland from University of Georgia suggested these species may act as a reservoir for Lyme disease and the tick vector diseases.

Speaking of vectors, West Nile virus may be implicated in declining population numbers of the ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus). Climate conditions may become more favorable to mosquito vectors. Julie Menotti with Michigan Department of Natural Resources and her team investigated the presence of West Nile virus in dead and ill birds and recommended further studies. A study from Pennsylvania presented by Dominica Dec Peevy from Penn State covered landscape and mosquito characteristics and how they may influence risk factors for West Nile epidemics.

Sub-lethal exposure to rodenticides is common in bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) and golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos), as reported by Kevin Niedringhaus. Exposure was detected in about 83% of golden eagles and 76% bald eagles, but mortality was about 4%. The effects on the population, and on individual birds, needs to be evaluated. As rehabilitators, you may be able to record exposure levels and contribute valuable data to the ongoing inquiry. We know, in other species, that sub-lethal exposure to anticoagulant rodenticides can have drastic impact on individual animals, and the more data we gather, the more we can assess and mitigate the impact.

An exciting study on post-release monitoring in hummingbirds using RFID (radio-frequency identification) might inspire some creativity. Ruta Bandivadekar from the University of California, Davis described a study of hummingbirds in rehabilitation and what methodologies impacted survivability. Post-release monitoring was integral to the study, and showed that RFID and PIT tags can contribute significant value to the available data.

Moral of the story, WDA 2019: we are a team!

Collaborations are incredibly important, valued, and sought. Wildlife rehabilitators can contribute directly to the knowledge base of wildlife disease and should be active partners in investigations.

The study of wildlife disease has matured and evolved. In order to implement effective solutions policy-makers, community leaders, sociologists, socio-economic experts, economists and other experts need to be engaged and invited onto teams. Discovering and describing diseases should be based on impeccable scientific inquiry, but successful implementation of change, mitigation of problems, and practical solutions will require outside help. Wildlife health workers must not be afraid of engaging outside experts and pushing their own comfort zones. Teamwork, engagement, and empowerment of professional networks, local communities, and colleagues is the only way that we will all mitigate the current climate crisis and anthropogenic catastrophe. Wildlife rehabilitators need to embrace scientific method, sharing, and collaboration in order to protect the precious creatures and environments we love; and to which we owe a debt and duty.

– Pat Latas, board member

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.